One Big Ass

And the worst part is that you can’t ever run enough to rid yourself of it.

And the worst part is that you can’t ever run enough to rid yourself of it.

The Article: Why Did Roberts Do It? by David L. Franken in Slate.

The Text: Sometimes you just have to take one for the team. A wistful thought of that kind must have flitted through the mind of Chief Justice John Roberts today as he announced that the Supreme Court was upholding the Affordable Care Act by the slimmest of margins.

The lineup was a shocker: Roberts joined the court’s four moderate/liberal justices in upholding the act. Court-watchers knew Roberts would be in the majority, whichever way the case came out, but we expected Justice Anthony Kennedy to be there, too. He wasn’t: Kennedy joined fellow conservative Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito in a vehement (and—departing from court practice—jointly signed) dissent. Indeed, the chief justice was the only justice who cast a vote on the individual mandate that was contrary to the political position of the party of the president who appointed him.

Why did he do it? Quite simply, to save the court. As Jeffrey Rosen has noted, the ACA case was John Roberts’ moment of truth—and today’s opinion proves that Roberts knew it. In the aftermath of Bush v. Gore and Citizens United, the percentage of Americans who say they have “quite a lot” or a “great deal” of confidence in the Supreme Court has dipped to the mid-30s. A 5-4 decision to strike down Obamacare along party lines, whatever its reasoning, would have been received by the general public as yet more proof that the court is merely an extension of the nation’s polarized politics. Add the fact that the legal challenges to the individual mandate were at best novel and at worst frivolous, and suddenly a one-vote takedown of the ACA looks like it might undermine the court’s very legitimacy.

As Aer reminds us with this fresh summer track, too much depth can sometimes sink an otherwise pleasant vibe.

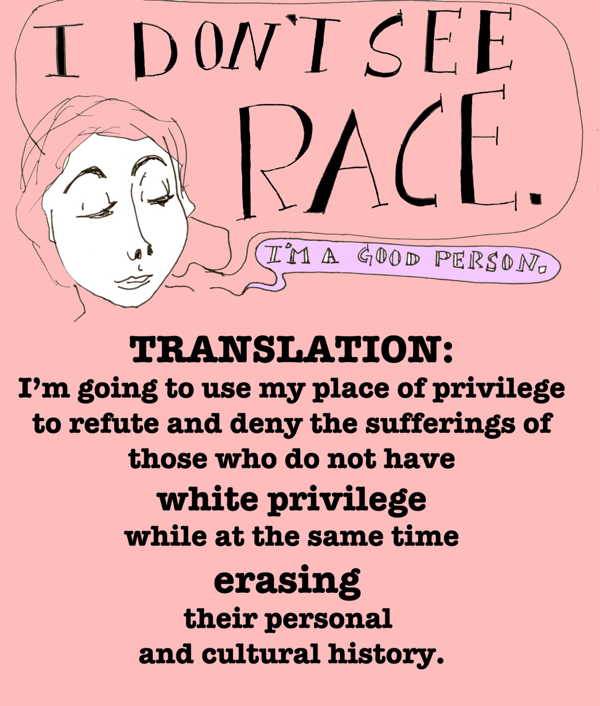

A preferred response would be, “I don’t see your intelligence,” but that probably wouldn’t be understood, either.

The Article: The Sharp, Sudden Decline of America’s Middle Class by Jeff Tietz in Rolling Stone.

The Text: Every night around nine, Janis Adkins falls asleep in the back of her Toyota Sienna van in a church parking lot at the edge of Santa Barbara, California. On the van’s roof is a black Yakima SpaceBooster, full of previous-life belongings like a snorkel and fins and camping gear. Adkins, who is 56 years old, parks the van at the lot’s remotest corner, aligning its side with a row of dense, shading avocado trees. The trees provide privacy, but they are also useful because she can pick their fallen fruit, and she doesn’t always have enough to eat. Despite a continuous, two-year job search, she remains without dependable work. She says she doesn’t need to eat much – if she gets a decent hot meal in the morning, she can get by for the rest of the day on a piece of fruit or bulk-purchased almonds – but food stamps supply only a fraction of her nutritional needs, so foraging opportunities are welcome.

Prior to the Great Recession, Adkins owned and ran a successful plant nursery in Moab, Utah. At its peak, it was grossing $300,000 a year. She had never before been unemployed – she’d worked for 40 years, through three major recessions. During her first year of unemployment, in 2010, she wrote three or four cover letters a day, five days a week. Now, to keep her mind occupied when she’s not looking for work or doing odd jobs, she volunteers at an animal shelter called the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network. (“I always ask for the most physically hard jobs just to get out my frustration,” she says.) She has permission to pick fruit directly from the branches of the shelter’s orange and avocado trees. Another benefit is that when she scrambles eggs to hand-feed wounded seabirds, she can surreptitiously make a dish for herself.

By the time Adkins goes to bed – early, because she has to get up soon after sunrise, before parishioners or church employees arrive – the four other people who overnight in the lot have usually settled in: a single mother who lives in a van with her two teenage children and keeps assiduously to herself, and a wrathful, mentally unstable woman in an old Mercedes sedan whom Adkins avoids. By mutual unspoken agreement, the three women park in the same spots every night, keeping a minimum distance from each other. When you live in your car in a parking lot, you value any reliable area of enclosing stillness. “You get very territorial,” Adkins says.